The Eighth Crusade – The Unraveling of Wales – The Longbow & The Iron Ring – The Battle of Irfon Bridge – A New “Prince of Wales” – The Lombards in London – The Expulsion of the Jews – “An English Justinian” – The Model Parliament – Scotland’s “Coming of Age” – The Scottish Succession Crisis – The First War of Scottish Independence – The Sacking of Berwick – The Battle of Dunbar – The Scottish Insurrection – The Battle of Stirling Bridge – The Battle of Falkirk – William Wallace: The Man & The Myth– The Rebellion of Robert the Bruce

|

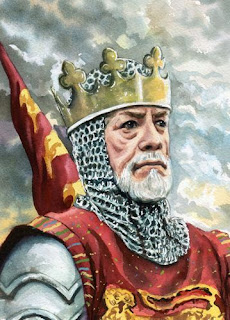

| An Aged Edward Longshanks |

Edward, in the days of his youth, had quite a reputation: he was, in the words of one contemporary, “arrogant, lawless, violent, treacherous, revengeful, and cruel.” He had the insufferable Plantagenet temper and no self-control to master it; but he matured during adulthood, and by the time of his coronation in 1274, he seemed a different person. Clocking in at 6’2”, Edward towered over his contemporaries, earning the nickname “Longshanks.” A contemporary gives us a character description of the man: he was “of swarthy complexion, strong of body, but lean; of a comely favour; his eyes in his anger sparkling like fire; the hair of his head dark and curled; concerning his conditions, as he was in war peaceful, so in peace he was warlike, delighting especially in that kind of hunting, which is to kill stags or other wild beasts with spears. In continency of life he was equal to his father; in acts of valour, far beyond him. He had in him the two wisdoms, not often found in any single; both together seldom or never; an ability of judgement in himself, and a readiness to hear the judgement of others. He was not easily provoked into passion, but once in passion not easily appeased.”

At only 11 years of age his father had married him to Eleanor of Gascony in order to settle an uprising there backed by Eleanor’s half-brother, Alfonso X of Castile; the King of Castile had knighted Edward at the wedding. Their marriage, though political in nature, became a story of friendship and romance, and Eleanor would bear him sixteen children: their first sons, Henry and John, died in infancy; their third son, Alphonso, was the heir to the throne and Eleanor’s favorite, but he died at age 12; and their fourth son, Edward of Caernarvon, would survive his father and take the throne as Edward II. Edward Longshanks ruled with a trusted friend and councilor, Burnell, by his side; and his wife Eleanor stood united behind her husband. Both Burnell and Eleanor managed to keep Edward’s temper in check, but Eleanor’s death from fever in 1290 at the age of 49 all but broke her husband. Edward collapsed into gloom, and those dreaded aspects of his youth began to creep back. When Burnell died in 1291, all bets were off, and Edward all but wholly reverted to his youthful ways: he quarreled with his clergy, put himself at odds with his barons, and began acting as a brute autocrat absent any royal limitations. The capriciousness, cruelty, and wanton violence of the last decade of his life overshadowed the temperate rule that had, up to that point, marked most of his reign. At the age of 60 Edward remarried, this time to the 17-year-old Margaret of France, daughter of Philip III of France. Their wedding was celebrated at Canterbury on 8 September 1299, and despite his age, Edward was virile: their first son, Thomas of Brotherton, became the Earl of Norfolk, and their second son, Edmund of Woodstock, became the Earl of Kent. Margaret and her step-son (who was only five years her junior) grew close despite Edward I’s pseudo-loathing of his future successor.

Though Henry III died in 1272, it would be nearly two years before Edward arrived in London to be crowned king. After his father’s victory in The Second Barons’ War in 1270, Edward departed for the Holy Land to participate in the Eighth Crusade. Edward’s great uncle, King Richard I, had won a name for himself in the Third Crusade, but England’s participation in the Fourth through Seventh crusades had been absent due to her internal turmoil (John’s wars against Philip II, and then the baronial revolts in his reign and in the reign of his son forced the English monarch and nobles to put crusading on the backburner). While John was in the process of losing the Angevin Empire to Philip II, Pope Innocent III called for the Fourth Crusade. Because western Europe’s heavy hitters—England, France, and the Holy Roman Empire—were embroiled in John and Philip II’s wars, the response to the Fourth Crusade was minimal. Those who agreed to go negotiated with the seafaring folk of Venice: the Venetians promised to sail them to the Holy Land and engender them with a year’s provisions if the crusaders would grant Venice half their conquests. Before they could war against the Muslims, however, the Venetians proposed to erase all crusader debt to Venice if the crusaders would be their sword-arm in settling a personal dispute against the Christian port city of Zara, which lie just across the Adriatic Sea from Venice. The crusaders, who were deeply indebted to the Venetians, put aside their scruples of warring against fellow Christians and agreed to get their hands bloody. Once the crusaders had agreed to take Zara, however, the Venetians proposed another city to take: that of Constantinople itself, the seat of the Eastern Orthodox Church and capital of the Byzantine Empire! The crusaders went along with the plan, and they marched on Constantinople. Innocent III, though not a fan of the Eastern Orthodox Church, did his best to prevent the crusade from getting entirely out-of-hand. His efforts were for naught, however, and the city, rendered weak by factional strife behind the walls, fell in 1204. The crusaders sacked the city and burned much of it to the ground. The Venetians and their crusader counterparts divided what remained of the Byzantine Empire into feudal principalities, and—for just over half a century—the Byzantine Empire was no more (in 1261 she would rise again like a phoenix from the ashes). The Fourth Crusade—which was really nothing more than Western Christians fighting against Eastern Christians—cemented the schism between the Western and Eastern Church.

The Fifth Crusade was well underway while John was begrudgingly assenting to Magna Carta at Runnymede; organized by Innocent III and his successor, Honorius III, the Fifth Crusade sought to reconquer Jerusalem, and it happened in two phases. The first phase consisted of an outright attempt to seize Jerusalem: armies led by both the King of Hungary and Leopold VI, the Duke of Austria, launched a failed attack on the Holy City. Later that year (1218) a German army with Dutch contingents allied with the Seljuk Turks in modern-day Turkey: the Turks, though Muslim, were hostile to the Abbuyid Muslims who controlled Egypt and Syria, and they would harass the Abbuyids from the north while the crusaders attempted an underbelly strike through Egypt. The crusaders successfully wrenched the port city of Damietta from Muslim hands, but they didn’t plan adequately for their march on Cairo: dwindling supplies forced them to turn back, and a nighttime raid by the enemy not only crippled the army but forced them to surrender. The subsequent peace talks led to an eight-year truce between the Abbuyids and western Europe. During the years 1228-1229, when a young and ambitious Henry III was following in his father’s footsteps to try and regain the lost Angevin Empire, the Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick II, did by the pen what the sword had not: he brought Jerusalem back into the fold of the Kingdom of Jerusalem for approximately fifteen years. His diplomacy with the Muslim leaders wasn’t born of piety but of personal gain: he had married the heiress of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, and if he could bring the Holy City back into the Kingdom’s hand, he—and not merely the Church—would benefit. Though he won Jerusalem in this so-called “Sixth Crusade,” the city would fall in 1244 to a people called the Khwarezmians, who had been displaced by the Mongols.

Four years after the fall of Jerusalem, and while Henry III was struggling for England against the conniving Simon de Montfort, the Seventh Crusade kicked off. King Louis IX of France spearheaded two disastrous expeditions into Muslim-controlled North Africa, and in March 1250, after his forces were annihilated at the Battle of Fariskur, Louis was captured. He fell ill with dysentery, but an Arab physician was able to cure him (the Arabs were light-years ahead of western Europeans in the field of medicine). He was ransomed in May, and he departed Egypt and headed directly for Acre, one of the only remaining crusader strongholds in Syria. Acre became as hotly-contested as the Holy City, and in 1270 Prince Edward of England participated in an attempt to relieve the Muslim pressure against the city. His adventures were catalogued in the Eighth Crusade.

|

| Edward on Crusade |

Prince Edward would be joined in the Eighth Crusade by his brother Edmund and cousin Henry of Almain. Edward and his young wife Eleanor departed from Dover, intent on rendezvousing with Louis IX in Christian-held Carthage on the North African coast. Louis died en route, and Edward rerouted to Sicily and bunkered down to weather the winter of 1270-1271. In March 1271, the fall-out from the Second Barons’ War reached the island: Henry of Almain was murdered by his own cousins, Guy and Simon, who were sons of the late de Montfort. Almain’s murder was family retribution for his beheading of their father and older brother at the cataclysmic Battle of Evesham. Edward was bent but not broken by his dear cousin’s death, and he forged ahead with the crusade. He and his brother Edmund, along with 1000 men, reached Acre in May. He was able to give Acre breathing space for a decade, and he raided the Muslim-held town of Quaqun and captured Nazareth, the birthplace of Jesus Christ. His military exploits, while praised at home and breathtaking in their retelling, were minor and inconsequential. In June 1272 Edward almost fell to an assassin’s blade: a Muslim assassin armed with a poisoned dagger attacked him, wounding him in the arm. The Prince managed to kick him off and subdued him with a bar stool. He was able to wrest the poisoned dagger from the assassin’s hands, but not before receiving a second wound in the forehead. Because the dagger was poisoned, his wounds could’ve been mortal, and it seemed they would be: his flesh grew black and rotted, and gangrene threatened to set in and spread throughout his body. If it weren’t for an excellent surgeon practiced in Arabic medicine, Edward would certainly have died—and English history would’ve taken a different turn. As it was, he survived, and when news arrived in 1272 of his father’s death, Edward was able to begin his return journey home to be crowned King of England.

Edward didn’t head directly home. He stopped en route at Paris to do homage to his cousin Philip III of France for his French lands, so he didn’t reach London until August of 1274. He was crowned on 19 August that year, aged 33, and he was given the regal name Edward IV (continuing the lineage from the Anglo-Saxon kings, which would certainly have received his father’s applause). Somewhere down the line he became known as Edward I, the first Edward King of England since the Norman Conquest. Historians can’t pinpoint any precise date for the transition; it was likely a gradual transition in the public consciousness rather than a legal “name change” decree. Edward’s reign, painted in broad strokes, can be divided into three “highlights”: his subjection and conquering of Wales, destroying once and for all its autonomy; his strengthening of the crown and parliament against the old feudal nobility (i.e. the barons); and the conquest of Scotland (though it would be a tempestuous conquest, marked by an unofficial rebellion led by William Wallace and, at the tail end of his reign, by an official revolt under the self-proclaimed Scottish king, Robert the Bruce).

At the beginning of Edward’s reign, most of Wales—which was populated by a ferocious albeit artistic people who claimed to be directly descended from the original Britons who had been pushed west by the Anglo-Saxon invasions—was a chaotic mosaic of small kingdoms in mountainous country. These kingdoms lacked stable borders, and their boundaries—and power—were constantly shifting through law (the custom of a sovereign dividing his lands among his sons) and the ambitious endeavors of individual rulers. The English kings claimed sovereignty over the hodgepodge of Welsh kingdoms, but this sovereignty was mostly in name only, accomplishing little in regards to actual control. In south and central Wales, Anglo-Norman barons—known as “Marcher Lords”—subdued the Welsh tribesmen on their borders; but in the north, Llewelyn the Last continued to rule his expansive kingdom of Gwynedd from the high mountains of Snowdonia. Llewelyn’s grandfather, Llewelyn the Great, had brought Gwynedd to prominence in Wales, resisting the English and bringing many smaller Welsh kingdoms under his hand. His northern “Welsh Empire” had waxed and waned in its running conflict against England, but Llewelyn the Last reached a milestone during the reign of Henry III: his territories were affirmed, he gained the official title “Prince of Wales,” and he was left to run his nation as a nominal vassal to the English king. By the time Edward took the throne, Llewelyn the Last seemed secure in the kingdom his father and grandfather had built; but when his arrogance clashed with Edward’s pride, the unraveling not only of Gwynedd but of all Wales was set in motion. Edward would do what all his predecessors had failed to do: incorporate Wales into the English nation.

William the Conqueror had hoped to subdue Wales, but the mountainous terrain, coupled with the ferocity of the Welsh fighters and their frustrating guerrilla tactics, made him abandon those ambitions. English colonization was relegated to the lowlands and river valleys of southern Wales, and though it was often sponsored by the Crown, it was undertaken by the so-called “Marcher Lords” (earls and barons whose territory bordered on Wales), who were fit to make their independent treaties—and wars—against the Welsh princes. Those lands that the Marchers conquered became private lordships outside the pale of normal English governance; but when Marchers became too powerful, English kings stepped in and brought them back to subservience. During England’s periods of instability—such as The Shipwreck in the 12th century and the baronial rebellions in the early 13th—resourceful Welsh princes capitalized on England’s weaknesses to recover lands that had been wrested from them. It was in the 1200s that Llewelyn the Great of Gwynedd, by a combination of force and diplomacy, became the virtual Welsh king over the rest of the Welsh kingdoms. The English kings chafed against his expansion, but their energies were divided between conflicts in the British Isles (particularly Wales) and conflicts in France (their attempts to recover the lost “Angevin Empire”). This changed, however, in 1259, when England’s rump government under Simon de Montfort, but with Henry III as figurehead, hammered out the Treaty of Paris, which ceded most of the Angevin ambitions to France. Though Henry III was able to come back to power, the Treaty of Paris still stood. It was a bittersweet thing, for though it forced Henry’s successors to find other avenues by which to claim the coveted and prosperous continental lands, it also freed the English kings to focus on matters closer to home: because Edward didn’t have to marshal his military against France, he could put his whole weight against any problems on the island. Thus when Llewelyn the Last foolishly refused to give Edward homage as required by the treaty he forged with Henry III, Edward could mobilize such forces that Llewelyn didn’t stand a chance.

|

| Llewelyn the Last |

Edward gathered a huge army in Worcester: the feudal levy itself comprised some 1000 knights armed head-to-toe, and a number of shires provided 15,000 additional foot soldiers, which included contingents of Welsh mercenaries and Gascon crossbowmen. In 1277 the invasion began: an all-out, three-pronged attack into Wales. He marched his main army up the northern coast of Wales and then up the valleys of the Severn and Dee, leaving a chain of fortresses in his wake. The guerrilla warriors of Wales opposed them in a number of skirmishes, and Edward became familiar with one of their peculiar weapons: the longbow. It was larger and more powerful than the English bows, and expertly crafted; it was “made of wild elm, unpolished, rude and uncouth” (according to one chronicler), and in the hands of a trained “longbowman” the longbow’s arrows could pierce chain mail and even pin a knight to his horse! The longbow became a dreaded weapon among the English, but Edward’s disposition towards it was more marked by fascination. Following the conquest of Wales, he would bring the longbow into the English army—and revolutionize England’s armies. Edward pressed deeper into Wales until he reached the mouth of the Conway River. Just off the coast, on the island of Anglesey—the “Lair of the Druids” that, with its fertile soil, had become the “breadbasket of Gwynedd”—Edward’s naval forces pounced. Anglesey fell to England, and the starvation of Gwynedd ensued. Edward’s forces blockaded Llewelyn in the Snowdonian heights, and the Prince of Wales was starved into submission. Llewelyn was stripped of all his conquests since 1247, and Edward built a ring of powerful castles around Gwynedd. He modeled these castles after those he had seen in the Holy Land, and this circle of fortresses became known as the Iron Ring. Those lands he’d wrested from the impoverished Llewelyn were incorporated into England and divided into shires and hundreds.

|

| The Battle of Irfon Bridge |

Llewelyn’s empire was no more; he was reduced to ruling a weakened and skeletal Gwynedd—but he didn’t let his ambitions go. He and Edward, though now at peace, chafed against each other, and the Welsh population in the conquered territories loathed their new English overlords. Unrest was kindled, but it didn’t catch flame until 1282 when Llewelyn’s brother, Dafydd (who had allied with Edward five years earlier and became known as a Welsh traitor) seized England’s Hawarden Castle and slaughtered its English garrison. As news of the uprising spread through Wales, more revolts followed, and Llewelyn, caught in the maelstrom, pitted himself against Edward and declared war on England. The fight for Welsh freedom was on, and at first it went in Llewelyn’s favor: the Welsh captured a number of Iron Ring fortresses, and they defeated an English force at the Battle of Llandeilo Fawr on 17 June. Edward’s lieutenant in Anglesey launched an impulsive attack across a bridge of boats spanning the Menai Strait, but his force was ambushed and torn to pieces at the Battle of Moel-y-don. Edward had hoped to quickly defeat Llewelyn, but these reverses made him take pause. Llewelyn took advantage of Edward’s breathing room by heading south into mid-Wales to rally support to his cause. Much of mid-Wales was dominated by the quasi-independent Marchers, and though several nominally supported Llewelyn, three in particular were diehard supporters of Edward and raised an English army supplemented with Welsh soldiers from one of Llewelyn’s political opponents. Their forces numbered around 5000 infantry-men (including archers) and 1300 heavy cavalry. This English-operated force marched towards Llewelyn, and the Prince of Wales took up position on a hillside north of the Irfon River to repel any attack across Orewin Bridge. His forces were likely comprised of a few thousand spearmen and javelinmen, some local archers, and a spattering of men-at-arms serving in his household guard; the sum of Llewelyn’s force likely numbered only 7000 infantry and just over 150 cavalry, putting him at a distinct disadvantage. On 11 December 1282, with his army encamped on the hillside before the bridge, Llewelyn decided to make a hurried trip to speak with some local leaders at Builth Castle. While he was gone, a local informant told the English about a ford across the Irfon two miles downstream from Orewin Bridge. The English archers crossed the ford, snuck up on the Welsh army, and began peppering them with arrows. The Welsh pivoted to drive them off, exposing their backsides and leaving Orewin Bridge undefended. They formed schiltrons—phalanx-like formations presenting the enemy with a solid hedge of steel—and the English cavalry, unopposed, stormed across the bridge and drove themselves into the Welshmen’s backsides. They couldn’t stand against the onslaught of arrows and the cavalry tearing through them like a knife through wet tissue paper, and they quickly disintegrated and routed—and at that very moment Llewelyn reappeared from his meeting at Builth Castle. He was cut off from his men and slain by an English man-at-arms named Stephen de Frankton.

|

| The Death of Llewelyn the Last |

The Welsh resistance collapsed with the death of Llewelyn the Last (a posthumous nickname). His severed head was delivered to London and displayed at the Tower. The traitorous Dafydd continued to lead the Welsh resistance, but he was betrayed in 1283 and handed over to Edward to be tried and executed. With his death any hopes of Welsh independence came to an end. This time Edward didn’t leave anyone sitting on the throne of Gwynedd—he demolished the kingdom in its entirety. The Statute of Rhuddlan in 1284 brought all of Wales into England’s administrative and legal framework; Edward reinforced and extended the Iron Ring, populating it with English settlers; and a last gasp Welsh uprising in 1294-1295 would be crushed, leaving Wales passive for more than a century. In 1301 Edward proclaimed his eldest son, Edward of Caernarvon, the “Prince of Wales.” To this day England’s crown prince is known as the “Prince of Wales.”

The successful conquest of Wales had cost money, and Edward employed two main avenues for paying for it: reliance on Italian bankers and dredging the Jews of every penny they had. Edward convinced Italian bankers from the Lombardy region of Italy to lend him money and facilitate customs duties; as part of their due reward he granted them land in London—the street where they set up shop is known as Lombardy Street today. Some historians argue that modern banking took its shape on Lombardy Street; terms like “credit” and “debt” were coined by the Lombardians, and the word “bank” probably derived from the Italian banco, which referred to the market tables and benches from whence the Lombardians traded. In these respects Edward’s reign can be seen as the launching pad for London’s commercial connection with banking. The second main route of financing the war effort against Wales—that of bleeding the Jews dry—began with the 1275 Statute of Jewry, which forbid Jewish people from lending money, cancelling all debts owed to them, forcing them to pay special taxes, and restricting them to earning money only as farmers or in select crafts. And just as his father had forced Jews to wear certain identifying insignia, so, too, did Edward: Jewish people were forced to wear a yellow star badge. Because Christians were forbidden from living among Jews, a Jewish part of London was built up—today it’s marked by the Old Jewry street. The Statute of Jewry remained in effect long after the conquest of Wales, and by 1290 Edward had reduced Jewish Londoners to poverty and had no more use for them. His “Edict of Expulsion” expelled the Jews from England: around 3000 were forced to pack their bags and leave, and 300 died in the process. Jews weren’t legally allowed to return to England until 1655.

|

| a depiction of Edward' I's parliament from 1524. Edward is flanked by Alexander III of Scotland and Llewelyn the Last of Wales |

Edward’s reputation as one of England’s best kings doesn’t come solely from his military exploits first in Wales and then in Scotland; indeed, his passing of good and wise laws and his reformation of royal administration and common law overshadow his nasty treatment of the Jews. His father had pacified England by putting down the Second Barons’ Rebellion, and Edward carried this pacification into the realm of English governance. His legal and administrative reforms and assertion of the rights of the crown helped bring stability to a country recovering from the throes of two civil wars. His advocacy of a uniform administration of justice and his codification of the English legal system earned him the nickname “The English Justinian” (after Emperor Justinian of the Byzantine Empire, who codified Byzantium’s laws). He issued the first Statutes of the Realm, which set a precedent for changing laws not by executive decision but by legislation. His statutes limited the money that English bishops could send to Rome and restricted the rights of the nobility and clergy in their exercise of private judgment in their own courts. The biggest of Edward’s administrative advancements was the entrenchment of parliament into England’s civic life. His military campaigns—first into Wales, and then in France and Scotland—required copious amounts of money, and because reliance on Italian bankers, while fortuitous in the short-term, led to heavy debts, and because the Jewish community could be squeezed only until they were rendered bankrupt, a more sustainable form of income was needed: taxes levied on the people of England. Edward’s father had spearheaded the evolution of parliament, prodding his Great Council towards a more established future, and Simon de Montfort took parliament a step further: by including lower-tiered members of society in the meetings, he mustered support for his short-lived baronial government and was able to publicize it throughout England. Edward was keyed in to de Montfort’s underhanded aims—de Montfort wasn’t interested in wider representation so much as he was determined to solidify his hold on the government—and Edward imitated it in his own parliaments. His goal, like de Montfort’s, wasn’t to share power but to strengthen royal authority and to infect England with a patriotic fervor. Throughout his reign he invited knights and burgesses to partake in his parliaments, and some parliaments—such as the Parliament of 1295, called the “Model Parliament”—included representatives from every shire and borough, as well as lesser clergy (this parliament gained its nickname because, after 1295, it became customary to “stack the house” with much more widespread representation). By the end of Edward’s reign, in 1307, parliament had cemented itself in English government, though it remained in its embryonic stages with undefined powers. Edward utilized these parliaments not only to authorize taxes (which, according to those clauses of Magna Carta that continued in play, needed to be approved by the barons) but also to promote legal, procedural, and administrative reforms.

At some point (historians are unable to give us a precise date) parliament was divided into two houses: the House of Lords included the tenants-in-chief (the immediate vassals of the king and upper-rank nobility), bishops, and the most politically astute abbots of English monasteries; and the House of Commons included two knights from each shire and two representatives from the boroughs. Though the House of Lords was preeminent, over time the House of Commons gathered more power. Historians believe the reason for this lies in two factors: first, the knights and lower-ranking barons sat with the town representatives (known as burgesses) and were forced to cooperate for their mutual interests; and second, though the bishops (the highest-ranking clergy beneath the archbishops) sat in the House of Lords, their interest in using parliament for their political ends began to decline (they preferred to do most of their heavy lifting in papal meetings). The first factor made the House of Commons become cogent, and the second rendered the House of Lords weaker—all to the benefit of the Commons.

The latter part of Edward’s reign was marked by his volatile conquest of Scotland. During the 1200s most of Scotland was ruled by the “King of the Scots.” The papacy supported an independent Scottish church, and Scottish kings occasionally acknowledged England as overlord, but this acknowledgement meant very little. It looked good on paper for the English monarchy, and it cost the Scots little. The Scottish kings were too powerful to be harassed by England’s northern Marcher Lords, and the Marcher Lords themselves had little incentive to attempt a piece-by-piece conquest of southern Scotland: the land, after all, was poor, and any conquest wouldn’t be worth its weight in both blood and money. Besides, conquering Scotland was one thing—keeping it conquered was quite another (as Edward and his successor would learn). The southern Scots, who lived in the lowlands (thus earning the nickname “lowlanders”) were close cousins to the English: many of the noble families, such as the Stuarts and Bruces, had migrated to southern Scotland from France during the Norman Conquest, being invited by the Scots because of their finesse at castle-building (a French phenomenon at the turn of the second millennium). Lower Scotland resembled England in many ways, not least because of the presence of burghs, abbeys, and cathedrals; castles in the English style had been built, and sheriffdoms—an Anglo-Saxon institution that had evolved under the Norman and Plantagenet kings—had developed to divide the lowlands into manageable administrative regions. Lower Scotland minted silver pennies on par with English sterling. Northern Scotland, however, was a different beast altogether: the northern Scots lived in the mountains (thus earning the nickname “highlanders”), and they were (supposedly) the direct descendants of the Picts and Scots whose ferocity had been meted out against the Britons in centuries past (remember that, according to legend, the Germanic Angles and Saxons were invited into Britain as mercenaries to protect the Britons from the Picts and Scots). However, more recent studies have shown that both the lowlanders and highlanders were heavily stocked with Scandinavian blood from the Viking incursions centuries prior. Though the border between Scotland and England was, for the most part, secure, there were aberrations; for instance, during The Shipwreck, King David of Scotland wrested Northumbria from England. Henry III, who had been more than amicable towards Scotland, solidified the English-Scottish border in the Treaty of York 1237. While English expansionism focused on continental territories in France, Scottish expansion looked north: the King of Scotland, previously confined to the lowlands, gradually expanded his rule northward into the highlands and incorporated much of the western seaboard. In 1266, in the Treaty of Perth, the King of Norway ceded the Western Isles to Scotland. By the end of the 13th century, Scotland was emerging from its “primitive” backwater origins and experiencing a coming-of-age onto the European political scene—and this is just when Edward got too involved in Scottish affairs and began a bloody and brutal war that would not only stretch into the reign of his son but also infect England’s toxic relations with France just in time for the Hundred Years’ War.

Edward’s brother-in-law ruled Scotland as Alexander III, but he died in 1286 in a tragic accident when his horse fell off a cliff with him in the saddle. The sole surviving member of his bloodline was his granddaughter Margaret, known as the Maid of Scotland. Edward schemed to marry Margaret to the Prince of Wales, Edward of Caernarvon; by doing so, he would politically unite England and Scotland, and it would be but a matter of time before Scotland was absorbed into England proper. The Maid of Scotland concurred, but a second tragedy struck in 1290: Margaret died before the wedding could take place. Alexander III’s royal line had been snuffed out, and now the Scottish throne was up for grabs. A host of claimants (many of them with dubious claims) jostled for the throne, and in 1292 the Scottish lords, hoping that Edward would be as favorable towards them as his father had been, requested the English king to arbitrate among them and choose his brother-in-law’s successor. Edward happily obliged, and his choice fell on John Balliol, who not only possessed a strong hereditary claim but who was, in Edward’s opinion, supple enough to be controlled. John Balliol became the next King of Scotland and swore allegiance to Edward. Edward knew he could push Balliol around, but his insistence on sovereign jurisdiction in Scottish courts congealed the Scottish nobles against him. Pinioned between pressure from Edward of England and pressure by his Scottish nobles, Balliol chose the less risky course and repudiated Edward’s claims. When Edward demanded that Balliol and his nobles support his campaigns in France, Balliol went the other direction: he and his nobles forged the Auld Alliance with the French in 1295, setting themselves against the English. They sealed the deal with an attack (albeit an unsuccessful one) on Carlisle Castle.

To say this turn of events enraged Edward would be an understatement; had his late wife Eleanor or late trusted council Burnell been at his side, perhaps his anger could have been cooled; but he was unchained, and nothing would hold him back. Vengeance was in the air, and in 1296 Edward mustered his royal forces and invaded Scotland, ushering in two and a half centuries of bitter hatred, brutal warfare, and savage border sorties. Right across the border into Scotland lie the royal Scottish burgh, Berwick upon Tweed. Berwick was Scotland’s most important trading port, and Edward set his eyes upon it. As his army appeared beyond the city gates, the Scottish townsfolk mocked the English king, poking fun at his “long shanks.” Edward, basking in the furious pride so characteristic of the Plantagenets, couldn’t stand for it: he mounted Bayard, his personal horse, and bounded across a ditch, leapt the town’s low palisade, and led Bayard into the heart of the town. The English troops poured into Berwick, and relentless house-to-house fighting spiraled into nothing short of downright massacre. The vast majority of Berwick’s inhabitants fell in the streets, their mocking grown quiet. The Scottish garrison at Berwick Castle surrendered, but by then Edward’s passions had slightly cooled: he let them live. Contemporary accounts of those slain in the Berwick Slaughter range from 4000 to 17,000, but regardless the number, news of the English atrocity spread throughout Scotland. Edward’s barbarity set off what would come to be known as the First Scottish War of Independence, and Berwick was followed by another victory in the Battle of Dunbar on 27 April 1296. Calling Dunbar a “battle,” however, is being generous: it was more along the lines of a cavalry skirmish between the English (under John de Warenne, the Earl of Surrey) and Balliol’s loyal cavalry (led by a nobleman named John Comyn “The Red”). Surrey came out on top, and the English host blazed a path through southern Scotland. Edinburgh Castle soon fell to Edward, and King John Balliol was captured and sent to the Tower as a prisoner. The capture of Edinburgh marked the beginning of an English occupation of Scotland, and to make the point that Scotland was no longer autonomous but owned outright by England, Edward had the Stone of Scone (a.k.a. the Stone of Destiny) whisked away to Westminster. Scottish kings since the Dark Ages had been crowned on this venerated relic, which had supposedly come from Palestine where it was Jacob’s pillow during his biblical dream, and Edward ordered it built into a special coronation chair at Westminster Abbey (in 1996, 700 years later, it was returned to Scotland). Edward had brought Scotland to heel in swift order, and he left the country populated by English garrisons. These garrisons would rule over Scotland with an iron fist, evoking ill sentiment that, in time, would overflow into outright rebellion.

But Edward had other matters to attend to. With another conquest notched into his belt, Edward crossed the Channel to deal with France. Louis IX, remember, had died of dysentery while crusading in North Africa; his son Philip took the reigns of France in 1271 as King Philip III. He died in 1285 to be replaced by his son (known as Philip IV). Both Philip III and Philip IV had cheated Edward of the benefits promised in the Treaty of Paris 1259, which had been forged by de Montfort’s temporary government and given with Henry III’s forced blessing. The French had undermined England’s authority in Gascony and nibbled at the territory’s borders. Edward had given homage to Philip IV in 1289, but the new French king stepped up his meddling in Gascony. Skirmishes between French and English sailors only embittered the situation. In 1293 Philip IV tricked Edward’s brother Edmund, who was conducting negotiations, into ordering a formal but temporary surrender of Gascony; Philip then refused to restore it to English sovereignty. Edward was delayed in responding to the French debacle because of the last gasp uprising of the Welsh, but upon bringing the Welsh to heel he crossed the Channel in 1297 to attack France from Flanders. His barons, however, whom he had increasingly ostracized in his descent into madness, refused to follow his lead. While trying to bring his recalcitrant barons into line in Flanders, Edward received news of an uprising in Scotland under a relatively unknown minor noble from the western Scottish lowlands named William Wallace. Wallace had capitalized on Scottish discontent, gaining support from numerous Scottish clans and even receiving pledges of loyalty from Scottish barons (though these barons had a tendency to shift their allegiance between Wallace and Edward depending on the way the wind was blowing and how the situation could be worked to their own ends). Wallace earned a reputation for “breaking English heads,” and though Edward saw Wallace as nothing more than a mere brigand, the fact that he and thirty of his followers had burned Lanark and killed its English sheriff showed that something a little more substantial than “brigandage” might be in play. This became apparent in the wake of the burning of Lanark: Wallace’s ragtag group swelled into a host of commoners and minor landowners, and they launched attacks on the English garrisons between the Forth and Tay rivers. Edward determined to keep facing off with the French, believing that the indomitable Earl of Surrey could put down the uprising before it swelled into anything more than a brushfire.

|

| William Wallace, as portrayed by Mel Gibson in Braveheart |

Back in Berwick, Surrey knew that Wallace and his horde of misfits were east of the River Forth and heading his direction. The safest way to cross the Forth was across a narrow wooden bridge at the Scottish town of Stirling. Surrey figured Wallace would try and take the town, which controlled the river crossing and was the English gateway to northern Scotland. The town’s weak garrison of English soldiers would be no match for Wallace, so Surrey marched out of Berwick and made a beeline for Sterling. Passing under the shadow of the town and approaching the bridge, Surrey saw Wallace’s Scottish host arrayed on the high ground just east of the narrow bridge. Under orders to put down the uprising as quickly as possible, Surrey gambled and decided to slug it out: the English troops, well-trained and provisioned, and far outnumbering the Scottish forces, would undoubtedly make quick work of the brigands. Or so he thought.

|

| The Battle of Stirling Bridge |

On 11 September 1297 Surrey met his match. The wooden bridge was just wide enough for two horses to cross abreast, and Surrey couldn’t ford the river elsewhere: to the east the river widened, and to the west it spread into marshland. The Scots waited patiently on the high ground as Surrey maneuvered his troops across the bridge. After about 2000 English soldiers—both infantry and cavalry—had crossed, Wallace ordered the attack. The Scottish spearmen poured down the hillside and fought off a charge by Surrey’s heavy cavalry. With the English cavalry scattered, the spearmen turned on the infantry. Once the Scots slashed through the harried English and secured the eastern side of the bridge, all English reinforcements were cut off. Caught on the low ground, with their backs to the river and their only route of escape held by the enemy, those English soldiers who had crossed Stirling Bridge faced nothing but massacre. A few hundred likely escaped by swimming back across the river, but the rest lie slaughtered on the shoreline. Realizing his cause was lost, Surrey ordered the western side of the bridge destroyed, and he led his ragged forces straight back to Berwick—leaving Stirling and its skeleton garrison exposed (it subsequently fell to Wallace). Many of Surrey’s panicked men became bogged down in a wooded marshy area and fell prey to a number of Scottish lords who seemed to emerge from the swampland like ghosts. The contemporary chronicler Walter of Guisborough reports that the English suffered 100 cavalry and 5000 infantry killed; among them was Edward’s treasurer for Scotland, Hugh de Cressingham. Cressingham’s body was flayed and his skin cut into small pieces for souvenirs; the Lanercrost Chronicle reports that Wallace had “a broad strip of his skin… taken from the head to heel, to make therewith a baldrick for his sword.”

|

| William Wallace wielding an axe against the English |

Having routed the largest English force in Scotland, the victorious Wallace carried the fight south across the border and into the English counties of Northumbraland and Cumberland. In a matter of mere months, through his practice of guerilla warfare in the name of Scotland, his name became synonymous with terror throughout England, and no one, it seemed, could stop him. He returned to Scotland triumphant in December 1297, and though he was the stuff of children’s nightmares in northern England, he was a hero in his homeland. He was proclaimed the Guardian of Scotland and tasked with ruling in the imprisoned King Balliol’s name. Except for two or three castles, the English forces had been swept out of England. Edward’s conquest was unraveling.

|

| The Battle of Falkirk: the first phase |

The English king couldn’t believe his ears when he heard of Surrey’s defeat at Stirling Bridge in September 1297, and unwilling to abandon his aims for Scotland, he put his French ambitions on hold (peace with France wouldn’t come until 1299 when Edward married Philip IV’s sister Margaret whereby he recovered the title to hotly-contested Gascony). Edward returned to England in March 1298, six months after Surrey’s whooping at Stirling Bridge, and by July he was marching into Scotland was an enormous army. On 22 July the English king faced off with the Guardian of Scotland at the Battle of Falkirk. Wallace’s force lacked archers and had only a handful of cavalry; most were spearmen drawn up in four phalanx-style formations called schiltrons. The schiltrons presented the enemy with a hedge of spears and were practically impervious to the cavalry charges so beloved by medieval knights. Edward’s knights, consumed with zeal and convinced of their superiority over the Scottish ruffians, charged the schiltrons even before Edward could array his army into battle order. English pride suffered a blow against the spearmen: the horses veered away from the bristling spears, and the knights didn’t make a dent. Wallace’s men felt like they had the edge in the battle, but Edward had an Ace up his sleeve: a contingent of Welsh archers armed with the dreaded longbows.

|

| The Battle of Falkirk: the second phase |

Welsh longbows had been the dread of English warriors in the final conquest of Wales, and Edward didn’t miss a beat incorporating them into his army. Soon the English would become masters of the longbow—so much so that the longbow would be synonymous with Englishmen—but for now the Welsh archers would do Edward’s dirty work. Longbows had a farther range than normal English bows (often called “short-bows” in the wake of the longbow’s adoption), and longbows packed a heavier punch. Edward ordered the archers to fire into the schiltrons at nearly point-blank range: the schiltrons withered under the harrying fire and became easy prey for Edward’s mounted knights. The knights, who had been beaten off in the first phase of the battle, now had free reign among the disintegrating schiltrons. The Scottish warriors broke but were run down. Wallace, with a spattering of fugitives on horseback, managed to escape. At the end of the day thousands of Scottish warriors had been slain, and the Battle of Falkirk was a crippling blow for Wallace: the glory days of his resistance were over, and his reputation was in tatters. Though Wallace’s reputation sank like a stone in the sea, Edward’s soared like an eagle: the massacre at Falkirk earned him the nickname Scottorum malleus, or “The Hammer of the Scots.” This nickname would become so entwined with his person that it would be chiseled onto his tomb.

The defeated Wallace resigned his title as the Guardian of Scotland, and he was succeeded by two noblemen, Robert the Bruce and Sir John Comyn “The Red”, and the Bishop of St. Andrews. Though the back of the Scottish independence movement had been broken, the insurgency continued, albeit on a smaller scale. Between 1298 and 1303 Edward managed to bring most of Scotland back under English dominion. Wallace continued his guerrilla warfare, and English garrisons were constantly on the lookout for him and his band of followers. In 1304 Wallace stormed Stirling Castle, which had been reoccupied by the English, but he was betrayed by one of his countrymen and handed over to the English. Edward ordered him paraded throughout England, where English folk peppered him with eggs and obscenities. He suffered through a trial from which there was no escape, and in 1305 in London he was hanged, disemboweled, beheaded, and quartered. Wallace was dead, but his reputation would live on. He has come to be revered as the preeminent Scottish hero, though many of the familiar stories of Wallace and his exploits derive not from history but from a late 15th-century romance penned by Harry the Minstrel. The late historian A.D. Innes writes, “Myths and legends swarm about [this] national hero who never bowed the knee to the foreign usurper. He was probably bloodthirsty, and he had suffered personal wrongs enough to make his bloodthirstiness excusable. But he stands out alone as conspicuously the one man who gave himself body and soul to the cause of Scottish liberty, and therefore the one who in Edward’s eyes was guilty of unpardonable crime.” The reigns of Scottish liberty would be picked up by one of the noblemen who had succeeded Wallace in leading Scotland: Robert the Bruce.

|

| a reconstruction of the face of Robert the Bruce, based off of skeletal remains |

Robert the Bruce, Scottish Earl of Carrick, had taken Wallace’s side during the Scottish insurrection. Bruce, along with John Comyn “The Red” and the Bishop of St. Andrews, took the reigns of rebellious Scotland. After quarreling with John Comyn and perceiving that the rebellion was doomed, Robert resigned from the leadership. In 1302 Robert bent the knee to Edward. Because of his submission to England, Robert was viewed with distrust and contempt by the die-hard Scottish patriots. He and John Comyn, one of the leading patriots, had a running feud that had started during their brief co-reign of quasi-independent Scotland. Despite his patriotic fervor, Comyn was made Lieutenant of Scotland by King Edward, though he was a man of two faces: he and Robert forged a pact whereby Comyn would renounce any of his claims to the Scottish throne and support Robert so long as Robert reinvigorated the Scottish uprising. Edward got wind of the plot and planned on arresting Robert while he was at the English court; an informant warned Robert of the impending arrest, and he fled back to Scotland. Comyn, it turns out, had been spoon-feeding Edward bits and pieces of their agreement in order to get Robert removed from Scotland’s political life. When the two met in the Church of Grey Friars in Scotland, Robert repaid Comyn’s betrayal by stabbing at the high altar. Two of his supporters stabbed him plenty more times to make sure he was well and truly dead. The murder of Comyn was an unpardonable crime, and Robert knew he faced grisly punishment at the hands of Edward; thus he had two choices: either submit to English justice as a traitor or revolt against England as a freedom fighter. He chose the latter.

In 1306 he was crowned independent King of Scots. He wasted no time in turning against the English, attempting to starve the English garrisons and capturing English strongholds. The second phase of the First War of Scottish Independence was now fully underway. A.D. Innes writes of Bruce, “Robert, the vacillating turncoat of the past, perforce transformed into the champion of Scottish independence, redeemed the sins and faults of his youth as the indomitable and magnanimous hero who fought and won against enormous odds the victory of Scottish freedom.” But in 1306 that victory was nowhere near a foregone conclusion; in fact, it looked doomed from the start! Bruce didn’t have a wide following (remember: he was loathed by many of the die hard patriots, and they didn’t trust him enough to throw in with him), and he was brutally defeated at the Battle of Methven on 19 June 1306: he lost 4000 men whereas the English lost only around 600. Bruce became a fugitive, and English justice was meted against his family: his wife and daughter were imprisoned by the English, and his two brothers were seized and beheaded. Bruce spent the winter of 1306-1307 in hiding, and come springtime he resumed his systematic raiding—and all the while he managed to escape the English, often by a hair’s breadth. He defeated the English at the Battle of Loudon Hill, and his star was on the rise.

Edward knew he would have to deal with Bruce as he had dealt with Wallace: by marching into Scotland with a vast army and personally crushing the revolt in a single pitched battle. But before he could reach the southern border, he succumbed to the bloody flux near Carlisle. He died aged 68 on 7 July 1307. As he lie dying, Edward fretted over England’s future in Scotland: he didn’t trust his heir, Edward of Caernarvon, to be successful in squashing Bruce’s rebellion and keeping Scotland in line. The young Edward was a bisexual whose interests lie in fine clothing rather than war; he would be easy prey to Scottish patriots. It’s rumored that Edward requested that his flesh be boiled from his bones so that they could be carried with the army on every campaign into Scotland, and that his heart be buried in the Holy Land where he had crusaded in his youth. These requests weren’t honored: he was buried, flesh intact, at Westminster Abbey, and his tomb is marked by a stone slab that reads Edwardus Primus Scottorum Malleus hic est 1306 Pactum Serva, which means “Here lies Edward, the Hammer of the Scots. Keep this vow.” His young widow Margaret left the hubbub of political life to keep residence in Marlborough Castle, and though she lived for another decade, dying at the age of 36, she never remarried.

Edward had good cause to worry about his successor. Comparing Edward I to his son Edward II, Robert the Bruce once commented, “I am more afraid of the bones of the father dead, than of the living son; and, by all the saints, it was more difficult to get half a foot of the land from the old king than a whole kingdom from the son!” Robert the Bruce would bloodily trump Edward II at the Battle of Bannockburn on 23 June 1314—and there Scotland would virtually ensure its independence from England.

No comments:

Post a Comment