|

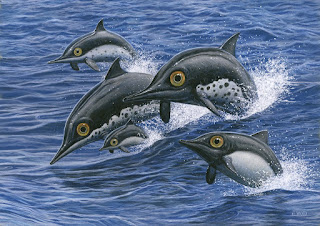

armored Henodus placodonts in a Late Triassic sea. They may look like sea turtles,

but they're of an entirely different stock. |

If a walrus and a turtle somehow found a way to mate, their offspring would probably look like a placodont. The first placodont fossils were discovered in 1830 and misidentified as belonging to pycnodont fishes; it wasn’t until Richard Owen came along that it was realized that Placodus actually belonged to a new group of reptiles. Today placodonts are classified as members of Sauropterygia, which also includes nothosaurs and plesiosaurs. Placodonts are unique among their sauropterygian brethren in possessing armor. Though the earliest placodonts were scantily-clad and resembled modern marine iguanas, the later developments looked like overripe turtles with a bony carapace that extended over the body and (in some cases) even partly down the length of the tail.

Placodonts – both armored and unarmored – showed up in the early Triassic. Because of the overall lizard-like body plan (and particularly the feet that still have toes), it’s believed they evolved from Permian lizards. Their immediate ancestors were probably beach-combing lizards that learned to dig in the sand and mud to unearth buried shellfish, and they may have raided tidal pools for shellfish or crustaceans. Ancestral placodonts probably started out with teeth similar to larger land-dwelling reptiles, but over successive generations evolution may have favored those with teeth better suited to a diet of shellfish. Those with forward-facing teeth would’ve had an easier go plucking shellfish out of rocky crevices in tidal pools, and those with robust rounded back teeth could’ve crushed the shells without worrying too much about dental ‘wear and tear.’ Evolutionists speculate that near-constant exposure to water – not to mention moving through it in the search for food – would’ve promoted adaptations like webbing between the toes to foster better marine movement while retaining the ability to move overland in search of various tidal pools.

|

| an unarmored Placodus |

Placodonts were relatively small creatures; most ranged between three and six feet long, and the largest clocked in around nine feet in length. In general terms they were short-limbed, robust animals that seem designed for life in shallow, near-shore environments. Their dense bones and (for some) armored plates made them negatively buoyant – like modern sea-cows, they wasted no effort in plodding along the seafloor in search of shellfish. Their small size and lack of a specialized marine body type indicates they were likely semi-aquatic in the sense that they could’ve clumsily lumbered onto the land to rest, breed, and escape marine predators. Placodonts come in two types – armored and unarmored – and the unarmored types had strong, square-shaped bodies; short, largely immobile necks; long, tapering tails; and thick, heavy ribs. Their upper limb bones were slender, and their hands and feet were short and weak. Their pectoral and pelvic girdles were located more underneath the body than to the side, and their vertebral column was weak; this meant they weren’t great at supporting their weight when on land, but they were able to use their limbs for steering and propulsion. It’s likely that their hands and feet were webbed. Armored placodonts tended to have broad, flattened bodies with low neural spines (unlike their unarmored counterparts) and short, paddle-like limbs.

All placodonts, both armored and unarmored, had robust skulls and rounded, flattened teeth in their jaws. The build of skull and muscle attachments indicate that placodonts pulled their jaw backwards as it closed, perfect for crushing shells against a battery of crushing teeth at the back of their jaws. Most placodonts – with the exception of a few advanced armored types – had protruding teeth at the front of the jaws designed for plucking shelled invertebrates from the thickest parts of the seafloor. Those types without these protruding teeth would’ve been relegated to fishing food from mud or sand. Placodonts fed by pitting mollusks between their enormous teeth, crushing the shell, spitting out the shelly parts, and swallowing the soft parts. Because of this feeding style, placodonts have often been regarded as reptilian analogues of walruses; now, however, we know that walruses don’t crush their mollusk prey, as once believed, but use a tremendous amount of suction to remove the soft parts from the shell. Though placodonts and walruses may have had similar diets, they had radically different means of getting to the ‘meat’ of their prey. Though it’s generally believed that placodonts fed exclusively on bivalves, some scientists have postulated that some species may have fed on crustaceans; others that they could’ve eaten brachiopods (but though brachiopods were abundant in placodont environments, they were nutritionally bankrupt).

|

| a placodont feeds along a shallow Triassic seafloor |

Because placodonts lacked flippers or propulsive tails, they would’ve been slow-moving and prone to predation by marine reptiles (such as ichthyosaurs and nothosaurs) as well as sharks. Large predatory fish called phytosaurs, and even early pterosaurs, may have preyed on placodonts. The earliest placodonts showed up in the early Triassic in tandem with primitive ichthyosaurs that were ravaging the oceans, and semi-aquatic nothosaurs lived along the coasts, competing with the placodonts in their home environment (sharks were growing bigger and meaner, too). Most paleontologists believe placodonts developed extensive armor carapaces as a means of defense against predators (one scientist, though, postulated that the carapaces were hydrodynamic adaptations to promote better aquatic movement; this must be rejected, however, because placodonts lack any other such features; any hydrodynamic benefits were a byproduct, rather than a cause, of the armored evolution). The presence of predators necessitated a type of defense, and just as turtles developed armored shells to protect them on land, so, too, did placodonts evolve carapaces to protect them at sea. A fully-grown armored placodont would’ve been a difficult meal for most predators; the common nothosaur, for example, had needle-like teeth designed for soft-bodied prey like fish. Such teeth would’ve easily broken on placodont armor (later types of nothosaurs, such as Simosaurus, may have been able to break through the armor with its blunt-shaped teeth). Fully-grown placodonts may have been able to live with only occasional threats from predators, but it would’ve been a different story for juveniles – as attested by the remarkable fossil remains of two juvenile Cyamodus placodonts in the stomach area of Lariosaurus, a small nothosaur. This fascinating discovery tells us two important things: first, not only were juveniles small enough to be swallowed, their shells may have been quite soft at this young stage (a feature commonly seen in modern shelled animals); second, the fact that two juveniles were found in the same predator before either of them could be digested indicates they were eaten at about the same time. This indicates that large numbers of Cyamodus were active at the same time, which further suggests that Cyamodus (and, by extension, placodonts in general) had an r-strategy for survival: large numbers of young were raised, but they had to fend for themselves absent parental care (like modern sea turtles). Though we don’t know the breeding and nesting habits of placodonts, one can easily envisage a Triassic beach in which thousand of baby placodonts scurry from their sandy nests and dodge pterosaurs on their lurch for the sea – and those that made it to the waters would then have to fend against carnivorous fish, nothosaurs, ichthyosaurs, sharks, and all hosts of predatory creatures. Juvenile mortality would’ve been high, but those few armored placodonts that made it to adulthood would reach a point where they could live and feed without much threat of an untimely demise in a predator’s stomach. The armored carapace may not have been the only line of defense: some paleontologists speculate that placodonts could’ve burrowed into the seafloor like modern rays to escape predators. The exposed carapace of armored placodonts would still be a tough nut to crack.

|

| the unarmored Placodus with a row of scutes along its back |

Placodonts have been divided into two major groups: the Placodontoidea and the Cyamodontoidea. The former, sometimes called ‘the unarmored placodonts,’ were less modified than cyamodontoids and retained a typically long reptilian body and a relatively tall and narrow skull. Though they lacked an extensive covering of armor plates, they did have armored scutes growing atop their neural spines, giving them an appearance similar to the modern marine iguana. Only two placodontoid genera have been recognized: Paraplacodus and Placodus. The first was described in 1931 and has only one species, but the other – Placodus – is one of the best known and most common of all placodonts, and this genera has numerous species attested to throughout the whole of the Triassic. It seems even without an armored carapace, these placodonts were able to hold their own. Placodus had three robust, spatulate, forward-point teeth, and it was large (up to nine feet), bulky, and had a long tail. A row of scutes ran along the tops of its neural spines.

|

| Cyamodus |

The Cyamodontoids, or ‘the armored placodonts,’ had reduced or absent front teeth and (most poignantly) developed a turtle-like carapace composed of interlocking scutes (though only one of the three sub-groups, the Cyamodontids, had a plastron, or ‘under-shell’, protecting their bellies). Cyamodontoids are generally divided into three families: the Cyamodontidae, the Placochelyidae, and the Henodontidae. The Cyamodontids are represented by only one genus, Cyamodus, which has six species (and which we met earlier in the belly of the nothosaur). Cyamodus had a short skull with a reduced snout and incredibly wide and enormous temporal fenestrae (openings in the heart-shaped skull). The number of teeth different species to species, but all had two projecting front teeth (unlike the placochelyids). They had a broad, flattened body with a carapace of hexagonal to subcircular osteoderms. The carapace covered much of the neck and virtually the entire span of the forelimbs, and a separate armored plate covered the hips and base of the tail. The tail was short and covered in osteoderms (as were parts of the limbs). In 1993 a pair of scientists speculated that, because of its more strongly developed teeth, stronger limbs, and deeper body, Cyamodus was less bottom-dependant and more mobile than the placochelyids, perhaps even living in rougher waters or a more rocky environment.

|

| Psephoderma |

The Placochelyids have two genera: Placochelys and Psephoderma. These two types were united by notably triangular skulls, pointed rostra, and extensive carapaces. Both only had two pairs of front teeth (but they differed in number and placement of back teeth) and both lacked a plastron (a continuous armor shield on the underside of the body, as seen in modern turtles). Likely unable to pull prey from rocky substrates, and because they had flattened bodies and long, slim tails, they have been viewed as reptilian ray mimics that may have hidden in the seafloor to escape predators. Placochelys only has one species, and it has a wider, stronger skull than Psephoderma. It was well-suited for crushing hard-shelled prey, but it seems poorly designed for pulling prey from rocks. Some scientists have speculated that placochelyids may have had a horny beak, but this is pure speculation. Psephoderma had a slim and elongate rostrum and only reached around four feet. It had a notably flattened body covered by a carapace of interlocking hexagonal osteoderms and a caudal plate covering the pelvis and base of its long, slim tail.

The Henodontidae consists of only one genus, Henodus from the Upper Triassic. It was discovered in southern Germany in what was thought to be a semi-enclosed brackish or possibly freshwater lagoon. Henodus is the only placodont known to have inhabited a non-marine environment. Though it was assumed for decades that Henodus had completely lost its front teeth, a Henodus species with front teeth was discovered in the 1990s. Like the Placochelyids, Henodus lacked a plastron. It’s been theorized that the extreme variation seen in Henodus is due to isolation: Henodus became isolated in this ancient German lagoonal basin; free of predators and with a limited diversity of prey, it became super-specialized for foraging in the soft sediment of the lagoon floor.

|

| a Henodus relaxes on the shoreline after a hard day of eating mollusks |