The base of the Anisian (and thus the bottom of the Middle Triassic) is sometimes laid at the first appearance of the conodont

Chiosella timorensis; the top is at the first appearance of the ammonite species

Eoprotrachyceras curionii and the ammonite family Trachyceratidae. The Anisian is sometimes subdivided into four substages: the Aegean, Bythinian, Pelsonian, and Illyrian. During the Anisian, amphibians began to diversify into titanic beasts; the erythrosuchids remained popular, but the emergence of true archosaurs was threatening their dominance; the therapsids began to suffer as the reptiles became bigger and meaner, and our Permian holdout

Lystrosaurus disappeared. The oceans began to crawl with a wider array of creatures: the ichthyosaurs continued to diversify, and nothosaurs and placodonts took the stage.

|

| Eryosuchus, an eleven-foot-long monster amphibian |

We begin with the amphibians, who began to diversify from the temnospondyl stock.

Cherninia had an enormous skull up to four a half feet long; it likely reached up to fourteen feet in length.

Eryosuchus was a large predator that could reach up to eleven feet long, and its skull was over three feet long.

The first true archosaurs (a group that includes modern reptiles, crocodiles, pterosaurs, dinosaurs, and birds) emerged. One specimen,

Nyasasaurus, may even be the earliest known dinosaur. Examples of the emergent archosaurs from the Anisian include

Sarmatosuchus (one of the earliest proto-crocodilian species) and

Ticinosuchus. The latter was about ten feet long, and its whole body - even the belly - was covered in thick, armored scutes. Some studies indicate these scutes were staggered, alternating between several rows, but other studies insist that the scutes were aligned in neat rows of a one-to-one assignment of scutes to vertebrae.

Ticinosuchus' legs were placed under its body almost vertically; the design of its legs and ankles indicate that it was a fast runner. Fish scales have been preserved in the abdomen area of this animal, indicating that its diet included fish.

|

| Ticinosuchus on the prowl |

|

| an artist's rendition of Nyasasaurus |

The archosaur

Nyasasaurus is considered by many to be the earliest known dinosaur, beating the title out from under dinosaurs from the Carnian stage at the bottom of the Upper Triassic. The assertion that this is a 'true' dinosaur is due largely to the interior structure of the humerus, which indicates rapid bone growth that closely matches that of

Coelophysis of the Upper Triassic. Because remains are fragmentary, this assertion cannot be proven. What

is known is that

Nyasasaurus was an archosaur as well as a dinosauriform (part of the group that includes birds, non-avian dinosaurs, and several not-quite-dinosaurian proto-dinosaurs from the Triassic).

|

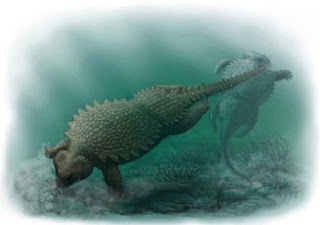

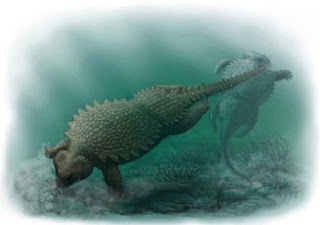

| a pair of Cyamodus placodonts |

In the Anisian oceans, ichthyosaurs continued to evolve, placodonts appeared (notably

Cyamodus and

Paraplacodus), and the thlattosaurs (or 'ocean lizards') evolved. The thlattosaurs were marine reptiles that lived during the Mid-Late Triassic. Some species grew over thirteen feet in length. They had long, flattened tails used in underwater propulsion. The species from the Anisian is

Askeptosaurus; this creature was thin and reached about six feet in length. It probably swam like an eel, dined on fish, and dived in deep waters (this assumption is based on the large eyes, which would enable it to see better in the deep waters, and from the protective bony rings around the eyes - later seen in ichthyosaurs - that prevented their eyes from getting squashed by water pressure at extreme depths).

|

| Ceresiosaurus |

Nothosaurs made their debut appearance in the Anian.

Keichousaurus was common in the Anian, and it could reach up to eight feet in length and had a long neck and long tail with elongated, five-toed feet. The pointed head and sharp teeth indicate it ate fish. Some recovered specimens feature an especially developed ulna (arm bone) that suggests it may have spent time on land or in marshes. Fossil evidence of a pair of pregnant

Keichousaurus indicates they had a mobile pelvis to give birth to live young.

Keichousaurus belonged to a group of small, primitive, aquatic reptiles called pachypleurosaurs that generally reached only about three feet in length (making

Keichousaurus a monster of the family). These creatures had small heads, long necks, paddle-like limbs, and long, deep tails. They're considered to be a subgroup of the Triassic nothosaurs. Another nothosaur of the Anian was

Ceresiosaurus. It was much more elongated than

Keichousaurus and reached nearly ten feet in length. It had close-but-not-quite fully-developed flippers with no trace of visible toes. It had multiple elongated phalanges, making the flippers much longer than what we see in later nothosaurs and more closely resembling those of the later plesiosaurs.

Ceresiosaurus also had the shortest skull of any known nothosaur, heightening its resemblance to plesiosaurs. Although it had a long neck and tail,

Ceresiosaurus probably propelled itself through the water much like a modern penguin. The discovery of pachypleurosaurs in the stomach region of

Ceresiosaurus indicates that it was a fast swimmer capable of catching fast-moving prey.

~ The Ladinian Stage ~

242 to 237 mya

Middle Triassic

The base of the Ladinian is defined as where the ammonite species

Eoprotrachyceras curionii appears; the top of the Ladinian is the first appearance of the ammonite species

Daxatina canadensis. During the Ladinian, most of life continued with business as usual, though there are a few noteworthy emergent creatures. These include the first absolutely-certain dinosauromorph,

Lagosuchus; another explosion of large therapsids; and the appearance of more large archosaurs, such as

Batrachotomus.

|

| Lagosuchus, a Ladinian dinosauromorph |

Lagosuchus is the first absolutely-certain dinosauromorph. As a dinosauromorph it isn't a true dinosaur, but it's closely related. It's known only from incomplete remains, but even so, these remains tell us that it was lightly built with slender legs and well-developed feet (all features it shares with dinosaurs). It could run on its hind legs for short periods, though it likely moved on all fours most of the time.

Lagosuchus was an agile predator that used speed to chase prey and escape predators. It was small, about the size of a ferret, and many scientists believe its metabolism was transitional between the cold-blooded reptiles and warm-blooded dinosaurs.

|

| a pair of Gerrothorax; note the 'toilet seat' action of the jaws |

Amphibians continued to evolve.

Gerrothorax was about three feet long with a remarkably flattened body. It probably hid under sand or mud on river and lake bottoms, looking for prey with its large, upward-facing eyes. It had an unusually shaped skull and angular protrusions on the side; in this way it looked like a primitive form of the Carboniferous/Permian

Diplocaulus, despite it appearing much later (a matter of convergent evolution).

Gerrothorax fossils have preserved bony gill arches near the neck, indicating that it was pedomorphic, retaining its larval gills into adulthood. It was once believed that these gills were external, like those of modern salamanders, but recent studies show that the gills were internal like those of fish.

Gerrothorax's bottom jaw was immobile; it opened its mouth by lifting its top jaw like a toilet seat. It's been argued that

Gerrothorax consumed prey using suction feeding; it had strong jaw muscles capable of both raising the cranium and lowering the jaw rapidly. The robust internal gill apparatus would've expelled water during this motion, creating intense pressure in the throat that would suck in small prey ideas. Bolstering this theory is the fact that the gill arches were covered in small denticles that would prohibit prey from escaping once devoured. Though suction feeding is common in fish and modern larval amphibians,

Gerrothorax breaks the mold by its lack of cranial kinesis (it couldn't flex its jaws against each other to consume prey).

Gerrothorax appeared in the Ladinian and disappeared in the Upper Triassic; during its long time-span it didn't evolve much, making it a rather static creature. It was well-adapted to its environment, but when the environment changed, it couldn't cope.

|

| the large amphibians Mastodonsaurus |

Another Ladinian amphibian was

Mastodonsaurus. This creature had a massive, triangular head that reached about four feet in length in the largest specimens. The total length of

Mastodonsaurus' body is thirteen to twenty feet. Its large, oval eye sockets were positioned midway along the skull, and its jaws were lined with conical teeth. Two large tusks projected up from the end of the lower jaw; these fit through openings on the palate and emerged from the top of the skull when the jaw was closed. It had a short tail, and its reduced limb bones had poorly developed joints. These 'devolutions' in the limbs, coupled with grooves on the head called sensory sulci, imply that

Mastodonsaurus was an aquatic animal that rarely left the water. Some paleontologists believe it was actually incapable of leaving the water; a fossilized 'graveyard' of these creatures suggests that a whole lot of them died en masse when pools dried up during times of drought. Though they likely didn't live in social groups, the dwindling water supply forced them ever closer together until they died like a family.

Mastodonsaurus lived in swampy pools and dined mainly on fish, whose remains have been found in this amphibians' coprolites. It may also have eaten terrestrial animals, such as small archosaurs, and the fossils of some smaller Ladinian amphibians bear tooth marks that may have been made by

Mastodonsaurus.

|

| a sculpture of a mother Exaeretodon and her pups |

Therapsids continued to get larger during the Ladinian.

Stahleckeria was an herbivorous dicynodont that measured about thirteen feet in length and clocked in around 880 pounds;

Dinodontosaurus was a smaller, beaked dicynodont that came in around eight feet long; and

Exaeretodon, one of the most common carnivorous Lanidian cynodonts, reached around six feet long. This latter therapsid used a special grinding action when feeding. That this animal was common is seen in the plethora of fossil remains from the time period. Remarkable fossil discoveries reveal that

Exaeretodon mothers gave birth to one or two calves, indicating a k-strategy for survival (in which the mother gave birth to fewer offspring but cared for them until they reached maturity).

|

| a digital rendition of Batrachotomus |

The archosaurs continued to evolve in the Lanidian, and

Batrachotomus was king of them all. This archosaur lived in a swampy region resplendent with horsetails, ferns, cycads, and conifers. Its remains have been found in close proximity to those of fishes, amphibians, and even nothosaurs. Its name comes from the Greek for 'frog cutting' and refers to how it preyed on the large amphibian

Mastodonsaurus.

Batrachotomus was a heavily-built predator that would've been fast and agile due to its erect stance. Its forelimbs were thirty percent shorter than its hind limbs, and it could grow up to twenty feet in length. Along its back was a row of paired, flattened bony plates attached to each vertebrae; these osteoderms were flattened and leaf-shaped, and extended from behind the head along the vertebral column, reducing in size until they tapered at the tail. There's some evidence that the osteoderms were also present on the ventral region of its tail (as is the case with its contemporary, albeit it geologically older,

Ticinosuchus) as well as on the flank, belly, and limbs. Many scientists speculate that it was an early relative of the monstrous

Postosuchus, which would dominate the Upper Triassic.

_by_Fran%C3%A7ois-Andr%C3%A9_Vincent.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment